Sydney Gardens is a Grade II listed park, and contains many listed buildings and features of national significance.

Pleasure Gardens

Pleasure Gardens were fashionable across Europe in the 18th Century. Most famous of all was Vauxhall Gardens in London - Vauxhall came to be a general term for pleasure gardens and Sydney Gardens was originally named Sydney Gardens Vauxhall.

Sydney Gardens were open to anyone who could afford the entry fee. Thrilling entertainments such as grand firework displays, acrobats, dancing, concerts and balloon ascents awaited in the evenings, or during the day one might take tea, walk the gardens, read the London papers and dine on cold meats and pastries in one of the outdoor shelters known as Supper Boxes. You could also play cards, gamble and drink at the Sydney Hotel (now the Holburne Museum) or attend dances in the grand ballroom. Along with all of the entertainment on offer, a visit to a Pleasure Garden was the time to mix and socialise with minimal supervision, and maybe even meet a potential partner.

Bath New Town & The Pulteneys

Pulteney Bridge was finished in 1774, connecting the city of Bath to the land East of the Avon which was to be the ‘New Town’ of Bathwick, built on the Pulteney family Estate. Bathwick was envisioned as the pinnacle of Georgian town planning, with Great Pulteney Street at the core, rival to the grandeur of Edinburgh or London. Bath New Town was never finished due to financial issues, but we did get Sydney Gardens and one of the terraces, Sydney Place, which were planned to surround the entire Gardens. When viewed from above the deliberate alignment of Great Pulteney Street and Sydney Gardens is clear. The main drive which terminates at the winged Loggia at the top of the Gardens is a continuation of Great Pulteney Street, which is supposedly aligned with Twerton Roundhill, once thought to be of Pagan significance. On a sunny day you can stand in the Loggia and see all the way through the Holburne Museum foyer to the other side.

Sydney Gardens was originally designed by the architect Thomas Baldwin who was also responsible for designing the original Guildhall building, but after his bankruptcy and dismissal from the Bath Corporation, the work was carried out under surveyor Charles Harcourt Masters.

Why Sydney? The Gardens were named after politician Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney, who was also the namesake for Sydney, Australia and Sydney, Nova Scotia. He was heavily involved in British Colonial activities and trade, such as the establishment of the British colony in Australia and overseeing the East India Company from 1784-1790. The Pulteney family named the site after the Viscount in an attempt to gain political favour, but we don’t have any evidence that Sydney ever visited the Gardens, and he died in 1800.

Sydney Gardens opens!

Work on the site was begun in 1793, with the first tree planted in September of that year to much celebration – cannons and ‘strong beer’. The park opened in 1795 for walking, as the Sydney Hotel was not yet finished, and was big enough to hold 4000 people on gala nights. It was so popular it led to the closure of older Pleasure Gardens in Bath - Spring Gardens and Grosvenor Gardens.

What did the Georgians do for fun?

Harcourt Masters Plan of Bath 1800, courtesy of Bath Record Office

We can see features on the 1800 plan such as a bowling green, swings, labyrinth, and ‘moveable orchestra’ which can tell us about Georgian entertainment. The most dramatic feature was known as The Ride, a 15m wide track for horse riding which ran along the entire perimeter of the park. It was “macadamised” (a paving technique devised by John Macadam) which meant The Ride was suitable for all weather.

Guidebooks and newspaper reports from the time describe elaborate firework displays let off from the top of the Sham Castle, complete with moat, a mill wheel or water cascade, and a ‘Hermit’s Cot’ complete with model hermit. There was the Cosmorama which allowed you to view scenes of faraway lands and events as though in 3D by the clever use of lenses and lighting. Cosmoramas and panoramas were popular attractions at the time, before world events and foreign places were accessible to most people.

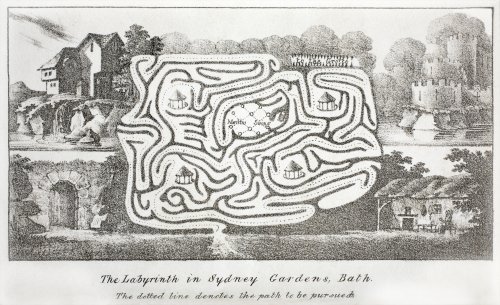

The Labyrinth was a particular source of fun in Sydney Gardens. Described as ‘nearly twice as large as that in the gardens of Hampton Court’ and frequented by Jane Austen, it was a meandering series of hedges and paths that ultimately led you out into the Grotto. The Grotto was constructed from local tufa stone, giving it an otherworldly air which the Georgians greatly enjoyed. Grottos were popular in many gardens and estates at this time, through to the Victorian period. In the centre of the Labyrinth was Merlin’s swing – created by the Belgian inventor John Joseph Merlin - a contraption for improving health through the effects of gravity. It was an adult sized swing, likely in the style of a boat-swing, perhaps for up to four people at a time.

Sydney Gardens was also host to some spectacular one-off events. In 1802 a hot air balloon was launched from the gardens. It ‘ascended from Sydney Gardens Bath on Tuesday, Sept 7. 1802, with Mr. Garnerin accompanied by Mr. Glassford… The Day being propitious they Continued their arial Voyage for an Hour & 50 Minutes. & then descended in a Field near Mells Park, the Seat of T. Horner Esq. 16 Miles from Bath. The greatest elevation they attained was 5420 Feet.' This was the early days of manned balloon flight in Europe and would have been quite the spectacle. It was of such significance that the 100th anniversary was celebrated by another balloon launch from Sydney Gardens in 1902.

'The Labyrinth in Sydney Gardens, Bath' from a Bath guide, J. Kerr, 1825

Jane Austen

Jane Austen lived at No. 4 Sydney Place between 1801 and 1804 and wrote of Sydney Gardens both in letters and several of her novels (Persuasion and Northanger Abbey). She visited the gardens regularly – missing the countryside she found solace in the quiet green corners of the gardens but was less pleased by the concerts and other noisy entertainments. When discussing the move to Sydney Place, she wrote jokingly to her sister;

“…there is a public breakfast in Sydney Gardens every morning, so that we shall not be wholly starved.”

And later wrote;

“Last night we were in Sydney Gardens again, as there was a repetition of the gala which went off so ill on the 4th. We did not go till nine, and then were in very good time for the fireworks, which were really beautiful, and surpassing my expectation; the illuminations, too, were very, pretty.”

The 19th Century

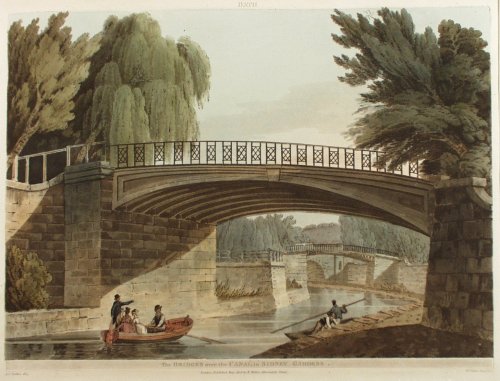

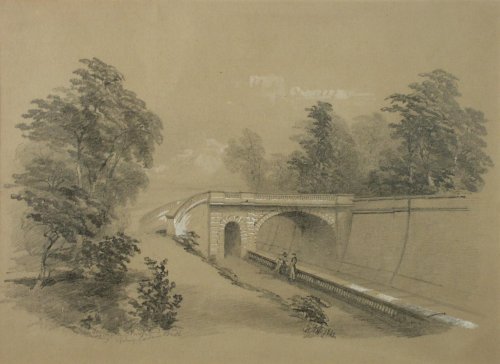

Within the first century of operation, three conspicuous and irreversible alterations were made to Sydney Gardens. First is The Kennet and Avon Canal constructed in 1800. Engineers determined that the only suitable route out of Bath was right through Sydney Gardens, which had not long been open. The proprietors struck a hard deal with the canal company, demanding £2,100 and the provision of two ornate Chinoiserie iron bridges over the canal, in exchange for cutting through Sydney Gardens. Even the road bridges over the canal are unsually elaborate, with ornate stone carvings representing the two major rivers of the South of England with the figures of Sabrina, Goddess of the Severn, and Father Thames watching over the waterway.

Bridges over the Canal in Sydney Gardens, c.1800 Nattes courtesy of the Victoria Art Gallery

The second disruption was Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Western Railway. Facing the same technical issues as the canal, the railway route out of Bath was cut through Sydney Gardens, and opened in 1840. In contrast with only 40 years earlier, the proprietors were keen for the intrusion as they thought the railway would be a gimmick to boost visitor numbers. It remains one of the most popular reasons for visiting the park today.

The Great Western Railway c.1861 by William Noble Hardwick courtesy of the Victoria Art Gallery

And finally in 1853 Bath Proprietary College took on the lease for the Sydney Hotel and in 1855 permanently separated the Gardens from the Hotel grounds by erecting a fence, which is now the Holburne Museum boundary wall.

A grim discovery

During the initial groundworks for Sydney Gardens a Roman tombstone was discovered, with the inscription;

'To the memory of Gaius Calpurnius Receptus, priest of Sul, aged 75. Set up by his wife . . . Calpurnia Trifosa.'

This was the tombstone of a priest of Sulis Minerva, dedicated by his wife, who we can tell from the Latin inscription was a freedwoman (former slave). At the Sacred Spring at Bath there were the Roman Baths, which you can visit today, and the Temple of Sulis Minerva. Priests like Receptus would have officiated ceremonies at the Temple and tended the flames that were kept burning around the statue of the Goddess Minerva.

Throughout the 19th and into the early 20th century, other indications of Roman activity were uncovered, including several stone coffins containing human remains, a coin, and decorated Roman pottery. It is likely that Sydney Gardens was once part of a vast cemetery on the outskirts of Roman Bath. A Roman coffin which contained a horse’s head was also discovered in Sydney Gardens. Horse burials are not uncommon in the late Iron Age and Romano-British period as horses were incredibly significant, but a lone horses head is an unusual find.

The 20th Century

By the late 19th Century the gardens were in decline, with a high turnover of proprietors, many going bankrupt or struggling to make the gardens profitable. Pleasure Gardens were falling out of favour and Bath was well past its fashionable heyday - the era of Beau Nash and the social excitement of Bath was in decline even before Sydney Gardens was opened. The Hotel had been sold off and separated from the gardens, and from 1916 housed the Holburne family collection. In 1910 the gardens were sold to Bath City Council and in 1913 re-opened as a public park, free for all to use.

Many of the current features of the gardens were put in during Council ownership…

The Temple of Minerva

The Temple of Minerva at the Empire Exhibition c.1911

Neither a real Roman temple nor a Georgian fake, it is a replica of the Temple to Sulis Minerva found at the Roman Baths – you can see the Gorgon’s head pediment of the temple on display at the Roman Baths. It was built in 1911 by A. J. Taylor to promote Bath stone at the Empire Exhibition at Crystal Palace in London, and was moved to Sydney Gardens two years later. There was some argument back and forth between Bath and Croydon Councils as to the cost of moving the Temple back to Bath, with neither side wanting to keep or pay for the building, but eventually Bath City Council paid up the £288 and it came to reside in Sydney Gardens.

The Gardens had held many of the 1908 Bath Pageant events, including grand firework displays, concerts, living chess, and a ‘Children’s Fairy Play’. Therefore it was considered appropriate to have a commemorative plaque to the pageant installed in the Temple of Minerva, although this has created some confusion as to the date and purpose of the building.

The Edwardian Toilets

In 1913 an iron ladies and gentlemen’s public convenience was purchased from William Farrer, Star Works, Birmingham for £190 2s. 6d. By 1920 the need for a separate Ladies’ toilet was proposed, and purchased from Walter MacFarlane of Glasgow. The original structure was then converted to become just for men by the addition of two sets of iron urinals. They are both Grade 2 listed buildings and early examples of prefabricated iron buildings. They are rare survivors – very few buildings of this style remain, especially not with interior fittings.

Peeling paint on the exterior of the Edwardian Ladies Toilet c. 2017

The Peace Oak

In 1919 there were celebrations all over Bath to mark the end of the First World War. In Sydney Garden the Peace Oak was planted by the then Mayor and Councillor Wills. In 2019 a new plaque was made and donated by Bath Freemasons, and re-dedicated in a public event in the park on Saturday 6th July, with Jane Tollyfield the granddaughter of Cllr Wills present, to commemorate 100 years since the peace celebrations, and the planting of the Concordia 'Golden Oak' in the park. A special booklet has been created about the history of the Peace Oak: download the digital PDF here.

In 1938 the Loggia was rebuilt in it’s current, reduced form. An original Georgian building, it had fallen into disrepair and the cost of a full restoration was considered too expensive at the time. Previously the wings extended much further, with carved cherubs on top of the columns.

Throughout the 1930s, 40s, and 50s Sydney Gardens was popular for its illuminations, concerts and flower shows. Sydney Gardens also hosted a very successful bowls club until its closure in 2015.

Despite everything we know about Sydney Gardens, there are still many questions to be answered, and mysteries to be uncovered. Will we find more Roman coffins? What was this area used for in Medieval times? What did the Cosmorama look like? Where were the Hermit’s Cot and Waterfall? What would it really have been like to walk the gardens in 1795? How different would it have been in 1895?

While there have been many changes in Sydney Gardens, elements remain from the early Pleasure Gardens; the distinctive hexagonal shape, the green lawns, the main drive and alignment with Great Pulteney Street, the remnants of the Loggia. People still enjoy watching boats on the canal and trainspotting, walking, picnicking, meeting and playing games, and there are still performances and concerts in the Gardens. It remains a green lung in the City of Bath, now a free space for all to enjoy.

Friends of Sydney Gardens Community Day 2018

Written by Hannah Myall

Hannah was the Heritage Intern on the Sydney Gardens Parks for People Project Development Phase. She has a background in Archaeology and Anthropology with a particular interest in burial rituals, and a growing affection for Georgian Bath.

Find out more

You can read about the history of Sydney Gardens on Wikipedia, on the Historic England Website, and all about Jane Austen’s fondness for the gardens.

Visit the Bath In Time website and search 'Sydney Gardens' to see more historic images, or why not visit Bath Record Office to look at early maps of the Gardens?

Read more about the heritage of the park on our Medium blog site through short articles, indepth essays and people's memories.